HIONJIN Fishing Gear Set: Elevate Your Fishing Experience with a Complete and Versatile Kit

Update on June 13, 2025, 10:40 a.m.

A Question on a Misty Morning

The air, cool and damp, carries the scent of wet earth and decaying leaves. Mist hangs over the water like a blanket, muffling the world in a soft, grey silence. In my hands, the fishing rod is a paradox—impossibly light, yet taut with latent energy. It feels less like a tool and more like a limb, an extension of my own intent. As I stand at the edge of the lake, a question surfaces with the rising sun: does this piece of advanced composite, a direct descendant of the aerospace industry, truly bring me closer to the wild heart of this place? Or does it simply wrap an ancient pursuit in a sterile layer of technology, distancing me from the very thing I came to find?

Echoes from a Wooden Past

To answer that, you have to travel back. Picture Izaak Walton, the patron saint of angling, by an English stream in the 17th century. His rod was likely a long, supple switch of hazel or a heavy, jointed pole. For him, and for centuries of anglers that followed, fishing was an exercise in profound patience and keen eyesight. A bite was a visual event: the sudden dip of a quill float, the tightening of a horsehair line. The conversation with the world beneath the water was conducted almost entirely through sight. The sense of touch was a blunt instrument, the rod a clumsy interpreter. It could haul a fish from the depths, but it couldn’t transmit its secrets.

The first great shift came after the Second World War, born from the same crucible of innovation that gave us radar and the jet engine. Fiberglass, a material of woven glass strands bonded in resin, created rods that were stronger, more durable, and cheaper to produce than the delicate, handcrafted split-cane rods of the elite. It was a democratic revolution. Suddenly, quality fishing gear was accessible. Yet, for all its strength, fiberglass was a poor conversationalist. It was stout and forgiving, but it had a muted soul. Holding a fiberglass rod was like trying to read braille with a gloved hand; the message was there, but it was muffled, indistinct. The underwater world was shouting, but we could only hear a roar.

A Whisper from the Sky

The true revelation—the moment angling learned to whisper—came from the sky. In the 1960s, in the pursuit of lighter, stronger, and more heat-resistant materials for jet engine components and rocket bodies, British engineers at the Royal Aircraft Establishment perfected a process for creating long, flawless strands of pure carbon fiber. This wasn’t just a new material; it was a new paradigm. Its secret lay in its highly ordered, crystalline atomic structure. Imagine it not as a tangled mess of fibers, but as a perfectly aligned, microscopic lattice—a structure practically designed to transmit energy.

I remember the first time I held one. It felt electric, alive. But the epiphany came on the water. I had spent years with the familiar, forgiving flex of fiberglass. On this day, with an early graphite-carbon composite rod in hand, I cast out a small lure. Minutes passed. Then, I felt it. It wasn’t the jarring tug of a committed strike. It was something else entirely: a faint, sharp tick. It was so subtle, so brief, that I almost dismissed it as my lure bumping a rock. But it was different. It was a nervous, living tap. On instinct, I set the hook and the rod bowed into a deep, satisfying curve.

That tiny signal, a message that would have been completely absorbed and lost in the dampening effect of fiberglass, had traveled up my line and through the carbon blank like a spark down a wire. In that moment, I understood. The world beneath the surface wasn’t silent; we just hadn’t owned an instrument sensitive enough to hear it. Carbon fiber was that instrument.

Anatomy of a Whisper

What I felt that day wasn’t magic; it was physics. The superiority of carbon fiber as a sensory conduit comes down to two key properties.

The first is its high Modulus of Elasticity. In layman’s terms, this is a measure of a material’s stiffness, or its resistance to being deformed elastically. Think of it like a guitar string. A loosely strung, heavy string produces a low, dull thud. But a thin, tightly strung steel string? It rings with a high, clear note. Carbon fiber is that high-tension string. It has an incredibly high stiffness-to-weight ratio, meaning it deforms very little under load and, crucially, snaps back to its original shape almost instantaneously. This efficiency, governed by the principles of Hooke’s Law, means that very little of a vibration’s energy is wasted as heat or internal friction. The signal arrives crisp, clear, and undiluted.

The second property is its incredible vibration transmission speed. Because of its rigid, ordered structure, vibrational waves travel through carbon fiber much faster and more efficiently than through the more chaotic, less dense matrix of fiberglass. It’s the difference between trying to hear a conversation through a brick wall versus a pane of glass. The message simply arrives with higher fidelity.

The Modern Symphony

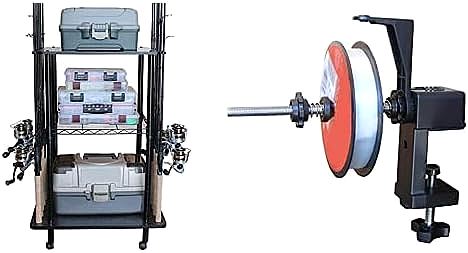

This brings us to the present, where that once-exotic aerospace material has become the standard. A complete package like the HIONJIN Fishing Gear Set is a perfect microcosm of this modern reality. It’s an entire orchestra of technology, designed to work in concert to perform one task: to translate the river’s pulse into a language we can understand.

The carbon rod, with its strong waist and sensitive core, is the conductor’s baton, setting the tempo and receiving the primary signal. But it doesn’t work alone. The spinning reel is a marvel of controlled friction, its drag system a finely tuned brake that allows a powerful fish to run without snapping the line, turning a brutal tug-of-war into a tactical dance. The fishing line itself, often a low-stretch synthetic, acts as a high-fidelity messenger cable, ensuring the whisper that begins at the lure isn’t lost in transit.

And the lures—from shimmering, wiggling soft baits to bionic crickets—are the spies, sent deep into foreign territory. They are masterpieces of biological deception, designed to perfectly mimic the movement, flash, and vibration of prey, exploiting the hardwired predatory instincts of fish, which often sense their world through a remarkable organ called the lateral line, a system that detects pressure waves and vibrations. Each component is a testament to our understanding of physics, mechanics, and biology.

The Angler’s Answer

So I stand here, in the quiet of the morning, and I have my answer. This sleek, black rod is not a barrier between me and the natural world. It is a bridge. It is a sensory organ I was not born with, extending my own nervous system from my fingertips, down its carbon spine, along the fine diameter of the line, and out into the cool, dark water.

This technology, exemplified in a modern, accessible kit, doesn’t make fishing easy. It makes it infinitely more complex and engaging. It allows us to hunt for things far more subtle than a fish for the table. We are hunting for information, for whispers, for a deeper connection. We are feeling the texture of the bottom, the nervous tap of a curious perch, the gentle sweep of the current.

The paradox is a beautiful one. A material forged in the heart of our most ambitious technological quests—to conquer the sky—has, in the end, grounded us more profoundly. It has given us the ability not to dominate nature, but to listen to it more intently than ever before. And in that quiet, high-definition conversation, we find the very thing we came for.