The $50 Tank: An Engineering Audit of the KastKing Rover Series

Update on Dec. 11, 2025, 4:54 p.m.

The narrative around fishing gear has largely been hijacked by the concept of “refinement.” Anglers are sold on the idea that smoothness equals quality, that silence equals power. But when you are standing on a mud-slicked bank at 2:00 AM, targeting a 40-pound Flathead Catfish that fights like a drowning bulldog, refinement is not just unnecessary—it is a liability. You do not need a scalpel; you need a hammer.

The KastKing Rover represents a specific philosophy in manufacturing: sheer mass over micro-tolerance. While Swedish legends like the Abu Garcia Ambassadeur have spent decades perfecting the synchronization of their level winds, the Rover (specifically the 40, 50, and 60 sizes) takes a brute-force approach. It is an unapologetic clone of the classic round reel architecture, but it strips away the heritage tax.

However, the question remains for the serious angler: Is this reel merely a cheap copy that will implode under hydrostatic pressure, or is it a legitimate piece of industrial machinery? To answer this, we cannot look at the marketing claims of “bulletproof” construction. We must look at the physics of the drive train, the thermal dynamics of the drag stack, and the material science of the frame. This is not a review of how the reel feels; it is an audit of how it works.

The Metallurgy of Torque: Brass vs. Polymer

The Shear Force Equation

In the world of baitcasting reels, the point of failure is almost always the interface between the main gear and the pinion gear. When a heavy fish makes a run, or when you are winching a fish out of heavy timber, the torque applied to the handle is transferred directly to these teeth.

Many entry-level reels—and controversially, even some sub-$70 “name brand” round reels—utilize polymer or nylon composites for their idler gears or even drive elements. Nylon is self-lubricating and quiet, which feels great in the store. But nylon has a low shear modulus. Under sudden, violent shock loads (like a striper hitting a topwater lure), plastic teeth do not bend; they strip.

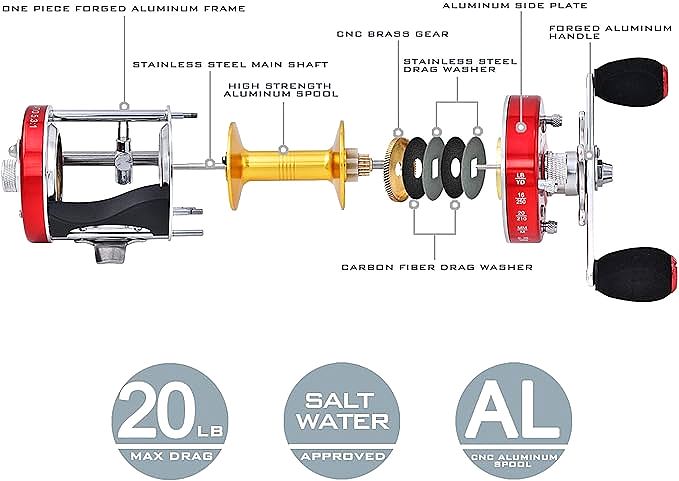

The KastKing Rover 40-60 series utilizes precision-cut brass gears. Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc. It is self-lubricating to a degree, but more importantly, it possesses a ductility that hardened steel lacks and a rigidity that aluminum cannot match in small gears. When you crank down on a Rover, you are engaging metal on metal. The feedback is more “mechanical”—you can feel the gears meshing—but this is a feature, not a bug. It means the transmission is rigid. There is no flex in the drive train, meaning 100% of your cranking power is converted into line retrieval.

The Frame Rigidity Variance

The Rover features anodized aluminum side plates. In 2025, “aluminum” is a buzzword, but the thickness matters. One of the primary issues with cheap round reels is “frame torque.” If the side plates are too thin, the entire frame can twist under heavy drag pressure. When the frame twists, the spool shaft goes out of alignment with the bearings, causing catastrophic friction and potentially snapping the shaft.

The Rover’s side plates are thicker than the industry average for this price point. While this adds weight (the Rover 60 is not a light reel), it creates a rigid cage for the spool. This is crucial for “lock-down” drag scenarios used in catfishing, where the reel acts more like a winch than a casting instrument.

The Thermodynamics of the “Cymbal Washer” Drag

Why Heat Kills Reels

When a fish pulls line against your drag, kinetic energy is converted into thermal energy (heat) via friction. If that heat cannot be dissipated, two things happen:

1. Fade: The drag material expands or glazes, reducing its friction coefficient. You lose stopping power right when you need it.

2. Sticking: The washer melts or bonds momentarily to the metal disk, causing the line to jerk. This shock wave travels down the line and snaps your leader.

Traditional budget reels use felt washers soaked in oil. Felt is smooth at low speeds but disastrous at high temperatures. It compresses and burns.

The Carbon Fiber Advantage

KastKing employs a carbon fiber drag system in the Rover, claiming up to 30 lbs of drag. Let’s deconstruct this. 30 lbs is an absurd amount of force—most rods cannot handle 30 lbs of static load without exploding. You will likely never use 30 lbs.

However, the benefit of a system built for 30 lbs is that it essentially “sleeps” at 10 lbs. Because the carbon fiber washers are designed to handle extreme thermal loads, they remain chemically stable during a long, screaming run from a Salmon or a Carp. The “Cymbal Washer” design likely refers to the curvature of the spring washers (Belleville washers) that apply pressure to the stack. This non-linear spring rate allows for a finer adjustment range at the lower end, meaning you can dial in exactly 3 lbs of drag for a delicate presentation, or crank it to “lockdown” for heavy cover.

The Competitor Matrix: Rover vs. The Swedes

The Architecture of Value

It is impossible to discuss the Rover without acknowledging the elephant in the room: The Abu Garcia Ambassadeur C3 and C4.

A teardown comparison reveals the stark reality of global manufacturing economics.

* The Abu Garcia: Uses higher quality stainless steel bearings (often made in Germany or Japan) and tighter machining tolerances. The fit and finish are superior. The level wind engages with a whisper.

* The KastKing Rover: Uses decent shielded stainless bearings, but the tolerances are looser. There is more “play” in the handle. The level wind makes a distinct mechanical sound.

However, looking at the structural components, the gap narrows. As noted by user teardowns (specifically the “Jim Presley” analysis), the Rover 60 compares favorably to the Abu 6500-S (the budget line). The 6500-S utilizes plastic components in the level wind drive to cut costs. The Rover retains metal.

This leads to a controversial conclusion: The KastKing Rover is likely more durable than the entry-level offerings of prestige brands, simply because it refuses to substitute metal for plastic, even if that metal is less refined. It is a tractor compared to a sedan. The sedan rides better, but the tractor pulls the stump.

The Specification Reality Check

The Line Capacity Discrepancy

One area where the “budget” nature of the Rover shows through is in quality control regarding specifications. User reports and independent measurements suggest the stated line capacity is optimistic.

For example, the claim of holding 219 yards of 20lb mono is mathematically suspect given the spool dimensions. Overfilling a baitcaster is a rookie mistake that leads to fatal backlashes. When spooling a Rover, one must ignore the box and watch the spool bevel. Leaving 1/8th of an inch of rim exposed is critical for braking performance.

The Bearing Count Myth

The Rover 60 boasts “6+1” bearings. In the fishing industry, high bearing counts are often a marketing gimmick. A reel with 3 high-quality Japanese bearings will outperform a reel with 10 cheap bearings.

However, the Rover’s placement of these bearings is strategic. They support the main shaft and the pinion gear, stabilizing the spool under load. While they may not spin for 2 minutes straight like a ceramic hybrid bearing, they are shielded stainless steel, providing necessary corrosion resistance for saltwater incursions.

In conclusion, the KastKing Rover is not a “magical” reel that beats $300 competitors. It is, however, a triumph of material allocation. By sacrificing silence, weight reduction, and brand prestige, it delivers a drivetrain capable of winching double-digit catfish for the price of a few lures.